GAA 1967.

SERVICE OF THE LAITY IN THE CHURCH AND THE COMMUNITY COMMITTEE

(Min. 58)

In one important matter remitted by the last Assembly, the Committee is glad to be able to report considerable progress. This concerns the doctrine of the Eldership and the admission of women to this service in the Church, about which specific recommendations are embodied in the Report, the proposed Deliverance, and an Overture which the Committee has submitted.

A Statement on the Eldership and the Admission of Women to that Office

This question has been studied closely by the Panel on Doctrine of the Church of Scotland, whose report was received by the General Assembly in May, 1964, and transmitted to the Presbyteries for consideration and comment. Of the Presbyteries which voted, 31 favoured and 11 opposed the admission of women to the eldership, there being 773 votes for and 496 votes against the proposal.

On the basis of these replies from the Presbyteries, the Panel on Doctrine recommended to the General Assembly that women be admitted to the Eldership and to a place in the Courts of the Church, and that the necessary procedure be implemented under the Barrier Act to remove the legal barriers rendering women ineligible for the Eldership.

The General Assembly accepted this recommendation and sent down an appropriate overture under the Barrier Act, which stated:

“The General Assembly, with the consent of a majority of Presbyteries, enact and ordain:

(1) Women members of a congregation shall be eligible for election and admission as Elders on the same terms and conditions as men members of a congregation.

(2) Act X of 1932 is repealed so far as it is inconsistent with this Act.” After careful study and consideration of the Church of Scotland Report,

your Committee decided to endorse it in general terms, as an adequate account of the origins and doctrine of the Eldership, and to append it to its own report as a basic study document.

The key question to be decided by the General Assembly appears to be: Does the doctrinal position of the Presbyterian Church of Australia permit it to adopt the Church of Scotland’s view of the Eldership ? In the opinion of this Committee the answer to that question is, Yes. The following reasons would support this opinion.

(1) Both Churches acknowledge the Word of God, which is contained in the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments, to be the supreme standard.

(2) Both Churches hold as their subordinate standard the Westminster Confession of Faith.

(3) The Church of Scotland explicitly, by Act of the General Assembly, February 10, 1645, and implicitly, in its Order for the Ordination and Admission of Elders, has accepted the doctrine of the Eldership set forth in the Westminster Form of Presbyterial Church Government under the heading “Other Church-Governors”. This paragraph, which is quoted verbatim in the Ordinal, states:

“As there were in the Jewish church elders of the people joined with the priests and Levites in the government of the church; so Christ, who hath instituted government, and governors ecclesiastical in the church, hath furnished some, beside the ministers of the word, with gifts for government, and with commission to execute the same when called thereunto, who are to join with the minister in the government of the church. Which officers reformed churches commonly call Elders.”

The Church of Scotland Report, Section 6, “The Westminster Assembly”, draws out the three clear implications of this paragraph (see appended Report).

(4) Although the Presbyterian Church of Australia has not explicitly approved the Westminster Form of Presbyterial Church Government, as has the Church of Scotland, it is quite clear that, in authorizing the use of its own Book of Common Order, in which is contained the Order for the Ordination and/or Induction of Elders, this Church has approved the doctrine of the Eldership set forth therein as being consistent with the Supreme Standard and the Subordinate Standard. As in the Church of Scotland Ordinal, the Australian Presbyterian Ordinal quotes verbatim the paragraph entitled “Other Church-Governors” from the Westminster Form of Presbyterial Church Government, and thus by implication this Church endorses the doctrine of the Eldership contained therein as being consistent with the Supreme Standard and the Subordinate Standard.

(5) Both Churches, in their Ordinals, set forth the functions of Elders in identical terms:

“The duties of Elders are more particularly:

To set the example of a virtuous and godly life, and of regular attendance at public worship;

To take part with the Minister in administering the care and discipline of the parish;

And to represent their brethren in Presbyteries and General Assemblies, when commissioned thereto.

(Note: The Church of Scotland Ordinal adds the word “Synods” between Presbyteries and General Assemblies.)

It is obvious from the foregoing, and from the appended Church of Scotland Report, that both Churches understand the Eldership as a function of responsible lay leadership within the Church. Neither Church, in explicit or implicit doctrinal statements, sees the Eldership as an inferior or lower order of clergy. For this reason the arguments which might be held to prevent the admission of women to the Ministry of the Word and Sacraments are simply not relevant to the question of the admission of women to the Eldership. If the Eldership is a function of responsible lay leadership, then it is clear that any communicant member deemed to possess the requisite gifts ought to be eligible for admission to this service in the Church, be that person male or female.

This Committee therefore believes that there are no valid theological objections to the admission of women to the Eldership in this Church.

As far as this Committee can discover, there are no legal barriers in the Code of the General Assembly of Australia against the admission of women to the Eldership. However, since a particular doctrine of the Eldership is being advanced, on the basis of which it is asserted that there are no valid theological objections to the admission of women to this office, and that it is a service in the Church which is appropriate for both men and women, then Barrier Act Procedure will be required to approve the doctrine proposed. To this end an Overture is being submitted to the General Assembly. Should the Overture be sustained, the Convener will move that it be sent down under the Barrier Act. If Clause 2 of the Proposed Deliverance is approved by the General Assembly, and the proposed Overture sent down under the Barrier Act, State Assemblies and Presbyteries will have full opportunity to consider the doctrinal basis of the Eldership set out in this report and the appended Church of Scotland report, and on the basis of these considerations to approve or disapprove the Overture.

Should the General Assembly accept the view that there are no doctrinal barriers against women serving as Elders, and the State Assemblies, at the request of this Court, take the appropriate steps to remove any legal barriers in their respective Codes, it would not mean that Sessions were obliged forthwith to accept women as additional Elders. It would simply mean that if and when a Sessions decided to add to its numbers, male and female communicants would be eligible for election on the same terms and conditions.

It is recognized by this Committee that much more study is needed on the question of the Eldership today. Thus it is not suggested for one moment that the Church in the 20th century should be content merely to repeat the doctrinal formulations of the 17th century. For example, the concept of “Church-Governors” in the Westminster Form of Presbyterial Church Government may suggest to some readers very little more than a Committee of Management, whereas in the context of the document itself it has a much richer meaning. It is absolutely essential that the paragraph on “Other Church-Governors” be read and interpreted in the light of the Preface, where government in the Church is set forth as the gift of the Risen Christ who “gave officers necessary for the edification of his church, and perfecting of his saints”. Nevertheless, the Westminster Form of Presbyterial Church Government does provide a sound doctrinal starting point from which the Church can proceed to restate and reinterpret the function of the Eldership in its life and mission in the contemporary world. The Committee proposes to pursue these studies on the function of the Eldership, believing that this is one of the most pressing problems confronting the Church. Although the task is enormous, your Committee is asking the Assembly for authority to tackle it.

B. Report of the Panel on Doctrine of the Church of Scotland May 1964

I. The Eldership

The Origins of the Eldership

John Calvin

The determining factor in the introduction of the office of Elder into the Reformed Church was the practice of John Calvin in the Church in Geneva.

In what he did, Calvin was influenced by three things:

(i) His study of the Early Church led him to the conclusion that the office of Elder had existed then, and was of value. (See below, section 4.)

(ii) He had knowledge of experiments which had been made in the introduction of laymen into the government and discipline of the

184

Church in centuries immediately preceding his own. Two of these were significant:

(a) In the Waldensian Church in the 13th century there were introduced “rulers of the people”. These were men appointed to assist in the discipline of the local congregation. (“Discipline,” Art. 4.)

(b) In the 14th century, the Bohemian Church appointed what were called “censors of morals”. These were laymen who, with the Minister, formed a disciplinary Court in the congregation. (“Confessio Fidei,” 1508.)

(iii) Calvin had many contacts with contemporary reformers. Oeco- lampadius in Basle and Bucer in Strasbourg had been influenced by the Bohemian experiment, and were working on similar lines. In 1538 Calvin came to Strasbourg to minister to a French congregation there and studied Bucer’s system.

This had a marked effect on Calvin’s thinking. When, in 1536, he had published the first edition of the “Institutes”, he made reference only to Pastors and Deacons, but when he came to write the “Ordonnances” of 1541, and the “Institutes” of 1543 he speaks of “Four orders of offices that our Lord instituted for the government of his Church”. (F. Wendel: “Calvin,” pp. 75-76.)

The “Ordonnances Ecclesiastiques”

The “Ordonnances Ecclesiastiques” were drawn up in Geneva in 1541, and these became the pattern for the Presbyterian form of government of the Church. (Text in “Calvin: Theological Treatises,” ed. J. K. S. Reid, Library of Christian Classics, Vol. xxii.)

In the “Ordonnances” Calvin outlined four orders of office within the Church. These were:

(i) Pastors for the preaching of the Word, and the right administering of the Sacraments, (l.c. pp. 58-62.)

(ii) Teachers and doctors, (l.c. pp. 62-63.)

(iii) Elders for the government of the Church and for discipline, (l.c. pp. 63-64.)

(iv) Deacons for the care of the poor. (l.c. pp. 64-66.)

Both Calvin and Bucer quote from Ambrosiaster (“Comm, on i. Tim. 5, 1,” Migne, P.L., Vol. xvii., 475D), to the effect that men similar to their “seniors” were once found in the Jewish synagogue and in the ancient Church, and this view was incorporated in the “Ordonnances”.

In his Geneva Catechism, moreover, Calvin speaks of Elders in these terms; “they should be chosen to preside as censors of morals, to guard against reprehensible offences, and to bar from communion those whom they do not believe to be capable of receiving the Supper, or to be admitted without profaning the Sacrament”, (l.c. p. 139.)

The “Institutes” and the “Discipline Ecclesiastique”

Calvin’s later view of the leadership is found in the “Institutes”, IV., 3, 8, and IV., 11, 1 in which he distinguishes two kinds of officers in the Council of Presbyters, “some who are ordained to teach, others who are no more than censors of morals”.

The Genevan Elders were appointed by the Little Council from among the town councillors, and were twelve in number. They joined with the Minister for the exercise of discipline in a Consistory, presided over by a “Syndic”.

In the “Discipline Ecclesiastique” of 1559, which became the basis of the French Protestant Church, Elders (anciens), and Deacons were to form the Senate of the Church, which was presided over by a Minister of the Word. (Section 20.) The office of the Elder is described as above, but the office of Deacon included the visitation of the sick, of prisoners and of the poor, catechising in the homes, assisting at the Sacraments, and reading the Scriptures and Prayers in the absence of a Minister. (Sections 20-24.) Elders and deacons were elected for one year.

Calvin’s Authorities

As already noted, Calvin in his effort to restore the “face of the ancient Catholic Church”, appealed to Ambrosiaster. He also quoted letters of Cyprian (numbers 45, 46 and 47).

185

These authorities can easily be added to. Origen states that among the Christians “some are appointed to inquire into the lives and conduct of those who want to join the community in order that they may prevent those who indulge in secret sins from coming to their common gathering .... They follow a similar method also with those who fall into sin, and especially with the licentious whom they drive out of the community.” (“Contra Cel- sum,” 3, 51, ed. Chadwick, p. 163.)

Further evidence for the existence of “seniores plebis” in the early Church can be found in the writings of Optatus (“De schismate,” 1, 17), in the “Gesta apud Zenophilum”, in the “Acta purgationis Felicis”, in the “Codex canonum ecclesiae Africanae” (caps, 91 and 100), and in Augustine (“letters,” No. 78). They are also referred to in Tertullian, and Isodore of Seville. These “seniores plebis” acted along with the bishops, presbyters and deacons in governing the North African Church. (See W. H. C. Frend, in the “Journal of Theological Studies”, N.S., xii., pp. 280ff.)

The Reformers, however, wanted more than the evidence of Church history for the revival of the office of Elder. They sought Biblical evidence, and Calvin claimed to find such evidence in i. Corinthians, 12, 28, in Romans, 12, 8, and in i. Timothy, 5, 17. From the Old Testament he quoted 2 Chronicles 19, 8.

The First and Second “Books of Discipline”

In 1556, when Knox returned to Geneva as Minister of the English Church there, he found “ruling elders” elected annually, who assisted in the government of the Church. This reflected the influence of the “Discipline Ecclesiastique” in which laymen appointed annually had their place in the Church courts.

Returning to Scotland in 1560, Knox brought about a change in the government of the Church, and, in the “First Book of Discipline”, consolidated its reformed policy. He was influenced in this by the practice of Bucer and of Calvin, and also by the “Ratio ac forma” of John a Lasco, a Pole who was for a time a Minister in London while Knox was living there. The other influence was that of the “Discipline Ecclesiastique” of 1559.

Under Knox, the election of the Elder and the Deacon “ought to take place every year, lest by long continuance of such officers, men presume upon the liberty of the Church” (Laing’s “Knox”, ii., 234). The duties of Elder and Deacon are largely those outlined in the “Discipline Ecclesiastique”, but the line between what the Elder did and what the Deacon did is less easily distinguishable.

In the “Second Book of Discipline” (1578), the work of Andrew Melville and his colleagues, there were changes in the theory of the office of Elder. It was a spiritual office, and was to be held for life though in fact annual elections continued to be held in some areas as late as 1719. The duties of the Elder are virtually the same as those of the Deacon in the French system. In contrast to the “First Book of Discipline”, the emphasis on the Elders’ supervision of the “life, manners, diligence and study of their Ministers” disappears, and the “Second Book” is more dependent than the “First Book” on i. Timothy, 5, 17.

The Westminster Assembly

At the Westminster Assembly, the Church of Scotland Commissioners and some of the Episcopalians were opposed on the one hand to the Independents, who sought to make the Eldership an office indistinguishable from that of the Ministry except in function, and on the other hand to certain Episcopalians who were suspicious of the whole idea of lay leadership in the Church. The debate lasted from 22nd November until 8th December 1664. By then a compromise was reached, and the office of Elder recognized as a spiritual office to which laymen are called and to which they are set apart to help in the government and discipline of the Church. The Scripture references quoted were ii. Chronicles, 19, 8; Romans 12, 8; and i. Corinthians, 12, 28: i. Timothy 5,17 was discussed at great length and finally rejected.

From these discussions three things emerge:

(i) Elders can only be read into the New Testament passages on the assumption that the Early Church had instituted something analogous to the “elders of the people” of the Old Testament.

(ii) What were called Elders at the time of the Westminster Assembly are what the Early Church more likely called Deacons.

(iii) The Westminster Assembly never refers to Elders “simpliciter”, but to “Other Church-Governors”, “elders of the people,” “commonly called elders”.

The Viewpoint of the Independents

The view of the Independents, who sought to make the Eldership an office indistinguishable from that of the presbyterate except in function- persisted after the Westminster Assembly and from time to time found individuals to champion it. It is strange that, whereas, when Elders were introduced into the Church, they were intended, among other things, to act as a check on the clericalism of the pre-reformation Church, a view of their office should be maintained which would in effect make them but another form of the same clericalism they sought to prevent.

The New Testament Evidence

.During the period of controversy the whole question of the Biblical evidence for the Eldership, as we know it in Scotland, was reviewed. Reformed scholars have overwhelmingly been forced to the conclusion that there is no clear evidence in the New Testament for what we call Elders today. The texts used for this purpose cannot be taken, when viewed objectively to bear this interpretation. They are never taken in this way by the Fathers of the Church. It is also true that, outside the Presbyterian Church, no Church reads the texts in this way.

If, however, Calvin and the Westminster Divines were right in their attempt to find Biblical authority for the office, then the best that can be done is to bring forward Biblical evidence for something like the Old Testament “elders of the people”, whose office was primarily a civic one, but who were associated with the religious leaders in the government of the Church. This office Calvin knew and employed; but Eldership as we know it in the Church of Scotland to-day he simply did not know. What appears to have happened is this. Elders in the sense of civic officials associated in the government of the Church no longer exist today; though for some time early in the Reformation there was an office of this kind in Scotland. But the idea of the association of laymen in the government of the Church was not abandoned; certain laymen were drawn from the membership of the Church itself and associated in the government of the Church. These laymen also discharged the duties proper to the diaconate of the New Testament. To these persons the name “Elder” was given, and to this office they are ordained and admitted.

The Deacons of the “First” and “Second Books of Discipline” seem to have played a very restricted part in the life of the Church of Scotland, as administrators of relief of the poor, and though the office was maintained in some congregations, in the majority it tended to disappear. From the time of the Secession onwards, however, some subdivision of the work of the Eldership began to appear, particularly in the congregations which formed the United Presbyterian Church, and in the Free Church, giving rise to other Church officials variously called “managers”, “deacons”, etc.

“Diakonos” and “Diakonein”

The study of the words “diakonos” and “diakonein” in the New Testament reveals the following. The words can best be rendered as “deacon” and “to deacon”. Originally no specific office was implied, and a development can be traced in the use of the words.

When Jesus used the word in St. Luke, 22, 27, He was simply describing the life He wished His disciples to live. He then immediately proceeded to “appoint” them “that they might eat and drink in His Father’s Kingdom”. Hitherto He had thought of Himself and His work as the service He owed to God, and to His fellows; the whole “deaconing” was being done by Himself. Now He appoints others to help with the work. But the specific work is not laid down nor is there anything “official” about the word as yet. As time passed, however, two things happened to these words, and what happened corresponded to the developing life of the Church.

“Deaconing” Diversifies

In Acts 6, 1-6 is recorded how the one ministry began to be diversified. Side by side with the primary and unique ministry of the Apostles, called the “deaconing of the Word”, there was instituted a secondary ministry dependent on it, called the “deaconing of Tables”. Many commentators equate “tables” with alms, poor relief, and the ingathering of funds for these purposes. But even so, this is not cut off from the “deaconing of the Word” and the Eucharist, since it is the gifts offered there that are, after the celebration, distributed. There is therefore a sense in which the two are complementary. Functioning together the “deaconing of the Word” and the “deaconing of Tables” make up the “deaconing” of the Church;; but there is now a two-fold “deaconing” discharged by different people. The one is performed by the Apostles, the other by the Seven appointed to assist them. The unique situation of Act 6 was not reproduced later.

“Deaconing” Bifurcates

The next stage is to be seen in i. Timothy 3, 1-12 (cf. Philippians, 1, 2). The total “deaconing” is still being discharged, but while there are still those who lead and those who assist in “deaconing”, leading in “deaconing” is being done by others than the Apostles.

In this there is not only a distinction of function in the total “deaconing” of the Church; there is imprinting itself upon the practice of the Church a distinction of office. Office is hardening out of function. What is happening is that “deaconing” has bifurcated into Overseer (i.e., Bishop) and Servant (i.e. Deacon), these words exactly representing the different functions discharged by each. So in i. Timothy 3, 2, Bishops are to “rule well”, and take charge of the Church, while Deacons are to “serve well” (v. 13). So also, Bishops must be “apt to teach”, (v. 2) while it is enough that Deacons should have personal piety and “hold the mystery of the faith with a clear conscience” (v. 9).

So now the offices, the Leader in “deaconing” and the Assistant in “deaconing”, together comprise in complementary fashion the leadership of the total “deaconing” of the Church. Men are the sole occupants of the first office; what they do is complemented by their assistants, among whom were certainly women.

Conclusions

The conclusion is that there is no clear Biblical evidence for the title “Elder” as we know it today. This is not to say that there is no Biblical warrant for the office. There is evidence in the New Testament of officials of the Church who did just what our Elders do today. These were the Deacons. This is to say that the best evidence for the Eldership is found in the teaching about Deacons. We note that other Presbyterian Churches, particularly the Presbyterian Churches in Australia, are being brought to similar conclusions. From this, certain practical questions arise, which might well occupy the attention of the Church.

What connection is there between the constitutions at present in force in the congregations of the Church of Scotland, and what appear to be the principles of New Testament Church organization? How far are we justified in subdividing the “deaconing” performed by the Eldership, and entrusting it to Managers, Board Members, or ordained Deacons ? How far do we see the Eldership today effectively fulfilling its task of service, of “deaconing” to the Church ?

Extract from—“Summary and Conclusions”

Women and Church Courts

As baptized persons, women are full members of the Body of Christ equally with men. This equal membership entitles them to take their part along with men when the Church acts corporately in taking counsel. This they will do, not as delegates of women in the Church, that is as speaking for the female part of Christ’s people, but in virtue of their baptism and so as representative of the corporate membership of the Church.

In the Church of Scotland as presently constituted, the courts in which the Church corporately takes counsel consist of Ministers and “Elders”. At this point it is the second component part of Church courts which is under discussion, and it is here that women should be given their place.

It is recommended that women be admitted to the eldership and thereby to a place in the courts of the Church.

C. Women in the Ministry

Progress in these studies has been slow for several reasons, not the least of which has been the difficulty of obtaining satisfactory study material from overseas. Several requests for information have gone completely unanswered, while others have been answered only after long delays, and even then the quality of some material sent has been very disappointing.

Since the Report to the 1964 General Assembly, several study documents on the question of the ordination of women have appeared. Of these the most notable are the Report of the Church of Scotland Panel on Doctrine, the World Council of Churches’ booklet, “Concerning the Ordination of Women”, and the recent Anglican Report of the Archbishops’ Commission on Women and Holy Orders. All three point to the very deep division of opinion within the Church Catholic on this subject. For example, when the Church of Scotland Report was studied by the Presbyteries, they were almost evenly divided on this issue, while the Report itself reveals a radical divergence of view among members of the Panel on Doctrine. The W.C.C. document carries sympathetic papers by Reformed writers, a critical paper by an Anglican writer, and two completely unsympathetic papers by Orthodox theologians. The Anglican Report again reveals the depth of difference on this issue, making it clear that within that particular Communion, there is no possibility of the ordination of women in the near future.

Perhaps the most disappointing feature of all these documents is the unsatisfactory argumentation. It is perfectly obvious that insufficient common ground for discussion has been mapped out, with the result that there is very little real meeting of the different points of view, and the great majority of the criticism of the opposing point of view simply miss the mark.

This difficulty is particularly noticeable in the use made of Scripture and Tradition. In the W.C.C. document the Protestant writers Andre Dumas and Marga Biihrig adopt views about Biblical authority and exegetical method that are markedly different from those of the Orthodox writers Nicolae Chitescu and Georges Khodre. The latter appear to use Scripture in a categorical manner, and are content to assert flatly that the Bible prohibits women from exercising priestly or ministerial functions within the Church. Both quote extensively from the Canons of various Church Councils to make it quite clear that this has been the consistent Orthodox interpretation of the Scriptural evidence over the centuries. Thus Chitescu writes, “Women cannot receive the sacrament of ordination in the Orthodox Church. The ordination of women is prohibited both by Scripture (I Corinthians 14: 34) and by the subsequent rulings of the Church” (Concerning the Ordination of Women, p. 57). Referring to passages in I Corinthians 11, 12, 14, and I Timothy 2, Khodre writes in similar vein, “These few lines taken from the teaching of the Bible are confirmed by the canonical tradition of the Church, which excludes women from the ministry,” (Op. Cit. p. 63). Where this kind of attitude is taken, it is painfully obvious that there is almost no basis for discussion.

By contrast, both Andre Dumas and Marga Biihrig appeal to Scripture in a very different and much more sophisticated way. Both subject the passages concerned to a very searching scrutiny, and advance some very impressive criticisms of traditional exegesis. Needless to say, the work of these two Protestant theologians will have to be examined equally critically before any firm conclusions can be drawn. In the recently published Report of the Archbishops’ Commission on Women and Holy Orders there is some strong criticism of Dr. Biihrig’s methods and conclusions which will have to be taken into consideration.

The Church of Scotland Panel on Doctrine submitted a report to the General Assembly in 1964, in which a fundamental disagreement was set out. “Some think that the traditional practice of excluding women from the special ministry was due to theological reasons which operated in the time of both the Old Testament and the New Testament and which therefore are still valid. Others hold that a change in the traditional practice of excluding women from the special ministry ought to be made because certain sociological factors that determined this practice neither apply today, nor ought any longer to perpetuate the exclusion” (Church of Scotland Reports, 1964, p.761 f.).

The writer originally intended to append the Church of Scotland Report to this Committee’s report as an interim study document. However further study of the document, together with correspondence from the convener of the Scottish study group, has convinced this writer and the Committee that the difficulties and confusions to which that document gave rise in the Scottish Presbyteries would be reproduced in Australia. The trouble lies not only in the terminology employed, but also in the anthropology which is basic to both sides of the argument. Closely following Karl Barth’s interpretation of Genesis 1.26 f (Church Dogmatics, III/l, p. 184 f), the Scottish Report asserts, “The basic unit of humanity is not the individual human being, male or female, but man-and-woman as one”. This relationship in Creation is maintained in Redemption, and Matthew 19: 5 is quoted in support of this assertion, i.e. “They twain shall be one flesh”, although no reference is made to Genesis 2: 24, the source of our Lord’s quotation. This writer finds himself in whole-hearted agreement with John McIntyre’s criticisms of this position when he writes (The Shape of Christology, pp. 108 ff.), “In brief, the case against women in the ministry was as badly stated as that for women in the ministry”. It is quite clear that the Scottish Report, in following Barth’s exegesis of the Genesis story far too closely, has misunderstood the Biblical writer’s account of the sexual differentiation between man and woman. Surely the Genesis writer is saying simply that whether one is a man or a woman, one is still created in the image of God, i.e. that sexual differentiation is irrelevant to our being created in the image of God or of being a specimen of the human race. By its particular use of the Genesis story, the Scottish Report has employed the sexual-marital relationship as the norm for understanding all man-woman relationships. This position needs only to be stated to be seen to be false.

In the 1964 Report this writer raised the question of the Christological consequences of saying that the Gospel by its very nature demanded a masculine ministry within the Body of Christ. It would seem that similar Christological consequences are involved if the basic unit of humanity is man-woman interpreted in terms of the sexual-marital relationship, for in this case the humanity of Jesus Christ would not be complete. He would not be one with us. The consequences of this situation for the interpretation of Scripture, the Nicene Creed, the Chalcedonian Decree, and for any satisfactory statement of the Atonement would be disastrous beyond description. John McIntyre (Op. Cit. p. Ill) spells this out very clearly when he writes: “It is no help to add, as some of Barth’s apologists have attempted to do, that in the Church as his bride, our Lord fulfils this requirement. To advance this kind of defence is to do one or other of two equally unacceptable things. Either, it is to make the Church part of the human nature which Christ assumed at the incarnation and so part of the incarnation itself, and such a view goes far beyond even Roman Catholic theories about the Church as the extension of the incarnation. Or, it is to say that Christ at the incarnation did not have this female element in his human nature but acquired it when he created the Church. Such a view would be an admission that the humanity which Christ assumed at the incarnation was defective.” When consequences of this magnitude are involved it becomes absolutely imperative that very close attention indeed be paid to exegetical method so that excesses of interpretation are avoided.

A further issue which is complicating studies on the issue of women in the ministry is what is currently called Church-World Relations. Many contemporary theologians are rightly insisting that the Church must be sensitive to the rapid changes taking place in the world where we live and in which the Church has its mission. Too often the Church has been and still is identified with the forces of entrenched power and conservatism; too often the Church has been and still is seen as being against humanity. God, if we understand the Bible in living, dynamic terms rather than fossilised, static ways, is involved in the tremendous social upheavals of our time, summoning His Church to be with him in what he is doing in the world. To do this, to respond in creative obedience to the call of Christ in the world today, will require much greater flexibility in the patterns of ministry than the Church has hitherto generally been prepared to accept. It may well be that the admission of women to the ministry of Word and Sacrament is one of a number of steps required in our time. So runs the argument. In its more extreme forms, the argument maintains that the very fact that so many spheres of work which were once closed to women are now rapidly being opened to them for full participation on equal terms with men is in itself sufficient evidence that God is summoning the Church to admit women to the ministry of Word and Sacrament.

Some such form of this argument seems to be assumed in the decision of the 1966 General Conference of the Methodist Church of Australasia to make provision in its laws to permit the admission of women to the ordained ministry. The minutes of the 1966 Methodist Conference refer back to a decision in 1932, “That Conference affirms the principle that an unmarried woman who believes herself called to the work of the ministry of our Church should be allowed to offer under the conditions prescribed in the Book of Laws”. At that time, and until the 1966 Conference, the practicability of putting this decision into operation was felt to present grave problems. However, the 1966 Report of the Standing Commission on Faith and Order, which had been instructed to report only on the practicability of admitting women to the ministry, concludes, “An examination of the practicability of the admission of women to the ordained ministry of the Church reveals no difficulties which cannot be overcome as we follow the guidance of the Holy Spirit”.

While it certainly must be acknowledged that the Church should always be prepared to discern the action of God in the social changes of the time, it does not follow that every social change is of God. There will inevitably be some social changes to which the Church will have to speak a decisive No! in the name of God. Hence the question now arises, By what criteria is the Church to judge whether or not a particular pattern of change in the community is of God ? Surely one indispensible criterion for such a judgment will be the Word of God given in Holy Scripture, “the only rule of faith and practice”. Where the Church for nearly 2,000 years has interpreted the Bible as prohibiting the ordination of women to the ministry of Word and Sacraments, it is simply not good enough to say that because all sorts of occupations are now being opened to women in our society the Church should follow suit. This is to treat a long and considered tradition of Biblical interpretation in a cavalier way, a course of action which is surely unthinkable for a church standing in the Reformed tradition. On the other hand, precisely because the Presbyterian Church belongs to the Reformed tradition, it must ever be open to reform under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, as new insights into the Word of God are given to it, and her present forms of ministry and structure are called in question. As a Reformed Church we must, on the one hand, be cautious about clambering aboard any particular theological bandwaggon that happens to come along and, on the other hand, be careful that we do not become content to stand still, allowing our thought to become hardened in set patterns. The words of Dr. Marga Biihrig aptly keep before us the need to respond adequately to the events of our time. She writes (Op. Cit. p. 51), “where Churches refuse to think consistently about the given relationship of men and women in the Christian Church, and in some way or other to make it real, then they will have to be questioned from “outside”, by the so-called world, about the basis of this attitude; and it may well be God Himself who is putting the question”.

This brief interim report has served to highlight the deep issues of Biblical interpretation and the edification of the Church for its mission in the world that are involved in the question of the admission of women to the ministry of Word and Sacraments. Here indeed, in this problem, we must carefully and prayerfully ask for the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

D. The Office of Deaconess in the Church

The Committee regrets having to report that it has been unable to carry out the instruction given at the 1964 General Assembly, Min. 153 (4). It has not been possible for this Committee to consult with the Committee on the Training of Women Workers, apart from a small exchange of correspondence. Should the Assembly renew its instruction to this Committee, efforts will continue to seek qualified people to undertake the studies requested by the Court.

E. The Laity, or People of God

The same problems which have prevented progress in the previous paragraph have held up work in this area. However several new names are proposed for membership on the Committee, with the specific intention of giving careful consideration to this immense field of study. It is this Committee’s hope that it will have something significant to report to the next Assembly.

A Note on New Nominations for Membership of the Committee

As several matters remitted to this Committee concern the place and service of women in the Church, it has been decided to nominate additional women members.

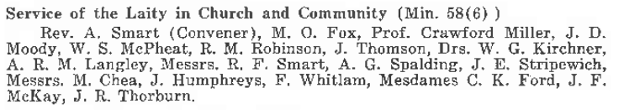

ALAN F. SMART, Convener.